Last Updated on March 12, 2025 by Bertrand Clarke

A growing body of evidence suggests that taking care of your heart might also protect your brain as you age. A recent study has uncovered a compelling connection between managing cardiovascular risk factors and potentially slowing the progression of brain-related diseases, such as Alzheimer’s. Published in JAMA Network Open, the research highlights how adopting a heart-healthy lifestyle could serve as a dual-purpose strategy, benefiting both the cardiovascular system and neurological health.

The study builds on the American Heart Association’s (AHA) Life’s Simple 7 framework, introduced in 2010 as a guide to improving heart health through seven modifiable lifestyle factors. These include maintaining a nutritious diet, staying physically active, achieving a healthy body weight, avoiding smoking, and managing blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar levels. While these steps are well-known for reducing the risk of heart attacks and strokes, researchers are now exploring their broader implications for brain aging.

Led by Anisa Dhana, MD, MSc, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Rush Institute for Healthy Aging at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, the study involved over 1,000 older adults from the Chicago Health and Aging Project. Participants, who were all aged 65 or older, underwent assessments to determine how well they adhered to the Life’s Simple 7 guidelines. More than half of the group identified as Black or African American, a demographic known to face elevated risks for both heart disease and dementia.

Participants were scored based on their adherence to the seven factors, with points ranging from 0 to 14. They were then grouped into three categories: low (0-6 points), moderate (7-9 points), and high (10-14 points) cardiovascular health. The researchers measured levels of a protein called neurofilament light chain (NfL) in participants’ blood—a biomarker that reflects nerve cell damage and is increasingly used to gauge brain health.

The findings were striking. Those with the highest cardiovascular health scores not only had lower NfL levels but also showed a slower rise in this biomarker over time as they aged. “NfL is like a warning signal for the brain,” Dhana explained. “When nerve cells are injured or stressed, this protein leaks into the bloodstream, offering a window into the brain’s condition. Our results suggest that a strong heart health profile could help protect against this damage.”

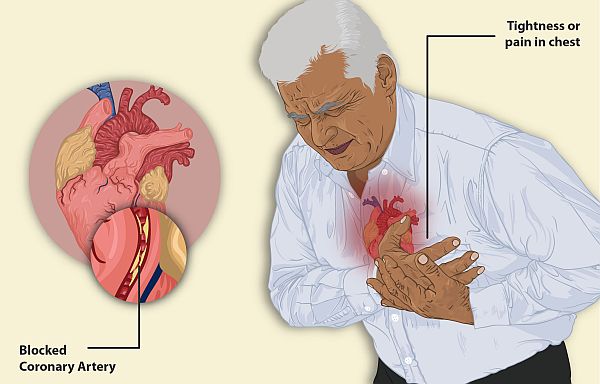

This discovery points to a possible overlap between the mechanisms driving heart disease and brain decline. Experts have long recognized that conditions like high blood pressure and diabetes harm blood vessels, including those supplying the brain. Over time, this damage may contribute to the development of neurodegenerative conditions. By addressing these risk factors early, individuals might not only extend their heart’s lifespan but also preserve their cognitive abilities.

The study also shed light on disparities in health outcomes. Participants with the highest cardiovascular health scores were mostly White, while Black participants were underrepresented in this group. This finding underscores a critical need for targeted outreach, as Black and African American communities face a disproportionate burden of both cardiovascular issues and neurodegenerative diseases. “Boosting awareness and access to heart health resources could make a real difference, especially for those at higher risk,” Dhana noted.

Cheng-Han Chen, MD, a cardiologist and medical director of the Structural Heart Program at MemorialCare Saddleback Medical Center in Laguna Hills, California, emphasized the broader implications. “This research reinforces the idea that what’s good for the heart is good for the brain,” he said. “As our population ages, reducing the incidence of conditions like Alzheimer’s could ease a tremendous societal burden. Focusing on underserved communities is especially vital to close these health gaps.”

The study’s findings resonate with a shifting understanding of brain health. “We once thought neurodegenerative diseases were purely genetic or inevitable,” said Jason Tarpley, MD, PhD, a vascular neurologist at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, California. “Now, we’re seeing how lifestyle factors tie into the picture. This research hints at a pathway linking heart and brain health that we can actually influence.”

While the results are promising, the study has limitations. It establishes a correlation, not causation, between cardiovascular health and lower NfL levels. To dig deeper, Dhana’s team plans to explore other brain-specific markers, such as amyloid-beta, a protein tied to Alzheimer’s pathology. They also hope to test whether interventions—like improved diets or exercise programs—can directly lower NfL levels and reduce neurodegeneration risk over time.

For now, the message is clear: small, consistent changes in daily habits could yield big rewards. Eating more vegetables, taking regular walks, quitting smoking, or keeping blood pressure in check aren’t just about avoiding a heart attack—they might also keep your mind sharp well into old age. “The beauty of Life’s Simple 7 is its simplicity,” Chen said. “These are steps anyone can take, and they might just add years of clarity to your life.”

As researchers continue to unravel the heart-brain connection, this study offers a hopeful glimpse into prevention. With neurodegenerative diseases on the rise, embracing a heart-healthy lifestyle could be one of the most powerful tools we have to protect our brains—and our futures.